Explosion rocks another Japanese nuclear reactor building

- NEW: A blast occurs Monday at the Daiichi's plant No. 3 reactor building, an official says

- NEW: The official says he doesn't believe there's been a massive radioactive leak

- IAEA says the radiation near the Onagawa plant "normal," may be from Daiichi

- Authorities have not confirmed meltdowns, because the reactors are so hot

(CNN) -- Fresh white smoke rose again Monday from Japan's Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, caused by an explosion at a building tied to the facility's No. 3 reactor.

Japan's Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano said that, according to the head of the nuclear facility, the container vessel surrounding the reactor is still intact. Initial reports suggest that radiation levels rose following the explosion late Monday morning, but Edano said he does not believe there has been a massive leak.

"We are now collecting information on the concentration of radiation," he said.

A wall of the building collapsed due to the blast, according to Japanese public broadcaster NHK, which showed plumes of smoke above the plant.

The secretary said that water continues to be injected into the plant's No. 3 reactor. That fact, and the pressure levels, has led authorities to believe that the reactor itself remains intact.

Officials: Radiation leak 'unlikely'

Officials: Radiation leak 'unlikely'  Nuclear expert talks to CNN

Nuclear expert talks to CNN  Physicist: 'Wide range' of possibilities

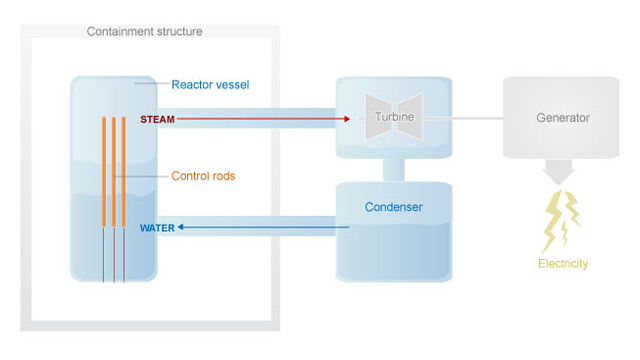

Physicist: 'Wide range' of possibilities  Explainer: Producing nuclear energy

Explainer: Producing nuclear energy The incident is the latest affecting the Daiichi, the hardest hit of several nuclear plants affected since Friday's 8.9-magnitude earthquake and subsequent tsunami.

Officials said that the explosion was likely caused by a buildup of hydrogen gas, similar to what had happened Saturday at the same nuclear plant's No. 1 reactor.

The 600 residents remaining within 20 kilometers (12 miles) of the plant, despite an earlier evacuation order, have been ordered to stay indoors, according to Edano.

Officials earlier said that they were operating on the presumption that there may be a partial meltdown in the No. 3 and No. 1 nuclear reactors at the Daiichi plant. Authorities have not yet been able to confirm a meltdown, because it is too hot inside the affected reactors to check.

The Tokyo Electric Power Company, which runs the plant, said in a press release late Sunday that radiation levels outside that plant remain high.

Japan's Kyodo newsagency, citing the same company, said that there were measurements of 751 microsieverts and 650 microsieverts of radiation early Monday. Both are above the legal limit, albeit less than one reading recorded Sunday. A microsievert is an internationally recognized unit measuring radiation dosage, with people typically exposed during an entire year to a total of about 1,000 microsieverts.

On Sunday, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano said accumulating hydrogen gas "may potentially cause an explosion" in the building housing the No. 3 reactor at the Daiichi plant.

At another plant, in Onagawa, authorities early Sunday noted high radiation levels. The International Atomic Energy Agency said later -- using information from officials in Japan -- levels returned to "normal" and found no emissions of radioactivity" from Onagawa's three reactors.

"The current assumption of the Japanese authorities is that the increased level may have been due to a release of radioactive material from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant" located 135 kilometers (about 85 miles) north of Onagawa, the agency said.

Japan's nuclear and industrial safety agency said late Sunday the wind was moving north/northwest -- which could carry airborne radioactive material near the city of Sendai and toward the Onagawa facility.

Most experts aren't expecting a reprieve of the 1986 Chernobyl meltdown, which killed 32 plant workers and firefighters in the former Soviet Union and at least 4,000 from cancers tied to radioactive material released by the plant. But in some ways -- especially the fact multiple reactors are affected, versus one in Chernobyl -- Japan's crisis is unique.

Nuclear expert: This is no Chernobyl

Nuclear expert: This is no Chernobyl  Anatomy of a meltdown

Anatomy of a meltdown  Radioactive leak? What to do

Radioactive leak? What to do  Japan's nuclear worries

Japan's nuclear worries "This is unprecedented," said Stephanie Cooke, the author of "In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age." "You've never had a situation with multiple reactors at risk."

These issues come despite Japan's solid reputation in the nuclear power field. Japan is heavily dependent on the energy source, with 54 plants and eight slated for construction, said Aileen Mioko Smith of Green Action, an environmental group.

Daiichi's No. 1 reactor -- the oldest of the six units at the site, according to World Nuclear Association, all of which are boiling-water reactors -- became operational in November 1970.

"Nuclear facilities in Japan ... were built to withstand earthquakes -- but not an 8.9 earthquake," said James Walsh, a CNN contributor and research associate at MIT's security studies program.

The crisis has stoked fears of a full-on nuclear meltdown, a catastrophic failure of the reactor core that has the potential for widespread release of radiation.

High levels of hydrogen, as evidenced at Daiichi, is one sign that a meltdown may be occurring. So, too, is the detection noted of radioactive cesium outside that plant, according to Toshihiro Bannai, an official with Japan's nuclear and industrial safety agency. This could be caused by the melting of fuel rods inside the reactor, indicating at least a partial meltdown.

Despite such evidence, Noriyuki Shikata, a spokesman for Prime Minister Naoto Kan repeated Edano's assertion that the situation is "under control" and said he would not describe what was occurring in the reactors as a "meltdown."

But Cooke, also editor of Nuclear Intelligence Weekly for the atomic-energy community, said she's not convinced authorities have a full handle on what she called "this hugely dangerous technology."

"The more they say they're in control, the more I sense things may be out of control," she said.

The Daiichi plant has a containment vessel, which theoretically would capture radioactive material if a full meltdown occurs.

In the meantime, government and power company officials are working to prevent even such a calamity -- even if it means rendering the Daiichi plant inoperable.

Authorities ordered the injection of sea water and boron into the affected reactors, even though salt and boron will corrode the reactor.

"Essentially, they are waving the white flag and saying, 'This plant is done,'" Walsh said. "This is a last-ditch mechanism to try to prevent overheating and to prevent a partial or full meltdown."

Edano has said there have been no leaks of radioactive material at any plants. Radioactive steam has been released intentionally to lessen growing pressure in the two Daiichi reactors -- in an amount authorities have described as minimal.

Still, on Sunday, Edano said nine people who were evacuated from near the Daiichi plant tested positive for high radiation on skin and clothing. This is in addition to at least three electric company workers who fell ill due to possible exposure, the Tokyo Electric Power Co. said in a statement.

Even if there's is no further catastrophe, the nuclear situation -- part of what Prime Minister Kan called the "toughest and most difficult crisis for Japan" since the end of World War II -- has clearly made an impact.

Cooke said that it may take years to fully assess the damage at the worst-hit reactors, much less to get them working again. And authorities may never definitively determine how much radiation was emitted, or how many got sick because of it.

Then there's the short- and long-term impact of Japan's electric grid: Soon after the quake, power was knocked out to 10% of Japan's households. Most of those people now have electricity, though experts say it is highly unlikely the most affected reactors will ever be operational again.

Beyond that, the crisis may have a significant impact the nuclear power movement. Walsh noted that while some countries, like China, may go forward in creating new reactors, others planned for South Korea, Turkey and elsewhere may pull back.

But assessing the far-reaching implications of the crisis isn't the top priority now. Instead, the focus is more on making sure that the situation does not deteriorate even further and put more lives at risk.

If the effort to cool the nuclear fuel inside the reactor fails completely -- a scenario that experts who have spoken to CNN say is unlikely -- the resulting release of radiation could cause enormous damage to the plant and/or release radiation into the atmosphere or water. That could lead to widespread cancer and other health problems, experts say.

Authorities have downplayed such a scenario, insisting the situation appears under control and that radiation levels in the air are not dangerous. Still, as what they described as "a precaution," at least 180,000 people who live within 20 kilometers (12 miles) of the plant have been ordered to leave.

"The bottom line is that we just don't know what's going to happen in the next couple of days and, frankly, neither do the people who run the system," added Dr. Ira Helfand, a member of the board of Physicians for Social Responsibility.

Sphere: Related Content

![Validate my Atom 1.0 feed [Valid Atom 1.0]](valid-atom.png)

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário