From Wall St to

Athens and Occupy sit-ins worldwide, protesters are wearing masks

inspired by V for Vendetta. Here, its author discusses why his avenging

hero has such potency today

A protester wearing a 'V for Vendetta' mask at Occupy Madrid on 15 October. Photograph: Action Press/Rex Features

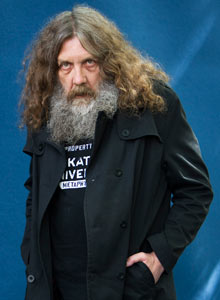

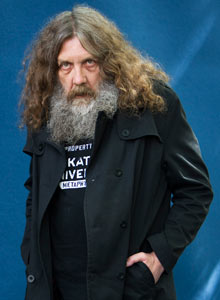

The comic-book writer Alan Moore

is not usually surprised when his creations find a life for themselves

away from the printed page. Strips he penned in the 1980s and 90s have

been fed through the Hollywood patty-maker, never to his great

satisfaction, resulting in both critical hits and terrible flops; fads for T-shirts, badges and shouted slogans have emerged from characters and conceits he has dreamed up for titles such as Watchmen and From Hell.

"I suppose I've gotten used to the fact," says the 58-year-old, "that

some of my fictions percolate out into the material world."

But Moore has been caught off-guard in recent years, and

particularly in 2011, by the inescapable presence of a certain mask

being worn at protests around the world. A sallow, smirking likeness of

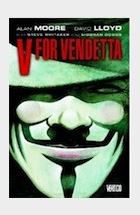

Guy Fawkes – created by Moore and the artist David Lloyd for their 1982

series V for Vendetta. It has a confused lineage, this mask:

the plastic replica that thousands of demonstrators have been wearing is

actually a bit of tie-in merchandise from the film version of V for Vendetta,

a Joel Silver production made (quite badly) in 2006. Nevertheless, at

the disparate Occupy sit-ins this year – in New York, Moscow, Rio, Rome

and elsewhere – as well as the repeated anti-government actions in

Athens and the gatherings outside G20 and G8 conferences in London and

L'Aquila in 2009, the V for Vendetta mask has been a fixture. Julian Assange recently stepped out wearing one,

and last week there was a sort of official embalmment of the mask as a

symbol of popular feeling when Shepard Fairey altered his famous "Hope" image of Barack Obama to portray a protester wearing one.

It all comes back to Moore – a private man with knotty greying hair and a magnificent beard, who prefers to live without an internet connection and who has not had a working telly for months "on an obscure point of principle" about the digital signal in his hometown of Northampton. He has never yet properly commented on the Vendetta mask phenomenon, and speaking on the phone from his home, Moore seems variously baffled, tickled, roused and quite pleased that his creation has become such a prominent emblem of modern activism.

"I suppose when I was writing V for Vendetta I would in my secret heart of hearts have thought: wouldn't it be great if these ideas actually made an impact? So when you start to see that idle fantasy intrude on the regular world… It's peculiar. It feels like a character I created 30 years ago has somehow escaped the realm of fiction."

V for Vendetta tells of a future Britain (actually 1997, nearly two decades into the future when Moore wrote it) under the heel of a dictatorship. The population are depressed and doing little to help themselves. Enter Evey, an orphan, and V, a costumed vigilante who takes an interest in her. Over 38 chapters, each titled with a word beginning with "V", we follow the brutal, loquacious antihero and his apprentice as they torment the ruling powers with acts of violent resistance. Throughout, V wears a mask that he never removes: bleached skin and rosy cheeks, pencil beard, eyes half shut above an inscrutable grin. You've probably come to know it well.

"That smile is so haunting," says Moore. "I tried to use the cryptic nature of it to dramatic effect. We could show a picture of the character just standing there, silently, with an expression that could have been pleasant, breezy or more sinister." As well as the mask, Occupy protesters have taken up as a marrying slogan "We are the 99%"; a reference, originally, to American dissatisfaction with the richest 1% of the US population having such vast control over the country. "And when you've got a sea of V masks, I suppose it makes the protesters appear to be almost a single organism – this "99%" we hear so much about. That in itself is formidable. I can see why the protesters have taken to it."

Alan Moore at the Edinburgh international book festival in 2010. Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian

Moore first noticed the masks being worn by members of the Anonymous group, "bothering Scientologists

halfway down Tottenham Court Road" in 2008. It was a demonstration by

the online collective against alleged attempts to censor a YouTube

video. "I could see the sense of wearing a mask when you were going up

against a notoriously litigious outfit like the Church of Scientology."

Alan Moore at the Edinburgh international book festival in 2010. Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian

Moore first noticed the masks being worn by members of the Anonymous group, "bothering Scientologists

halfway down Tottenham Court Road" in 2008. It was a demonstration by

the online collective against alleged attempts to censor a YouTube

video. "I could see the sense of wearing a mask when you were going up

against a notoriously litigious outfit like the Church of Scientology."

But with the mask's growing popularity, Moore has come to see its appeal as about something more than identity-shielding. "It turns protests into performances. The mask is very operatic; it creates a sense of romance and drama. I mean, protesting, protest marches, they can be very demanding, very gruelling. They can be quite dismal. They're things that have to be done, but that doesn't necessarily mean that they're tremendously enjoyable – whereas actually, they should be."

At one point in V for Vendetta, V lectures Evey about the importance of melodrama in a resistance effort. Says Moore: "I think it's appropriate that this generation of protesters have made their rebellion into something the public at large can engage with more readily than with half-hearted chants, with that traditional, downtrodden sort of British protest. These people look like they're having a good time. And that sends out a tremendous message."

It is an irony noted with relish by critics of the protests – one also glumly acknowledged by many of the protesters – that the purchase of so many Vendetta masks has become a lucrative little side-earner for Time Warner, the media company that owns the rights to Moore's creation. Efforts have been made to avoid feeding the conglomerate more cash, the Anonymous group reportedly starting to import masks direct from factories in China to circumvent corporate pockets; last year, demonstrators at a "Free Julian Assange" event in Madrid wore cardboard replicas, apparently self-made. But more than 100,000 of the £4-£7 masks sell every year, according to the manufacturers, with a cut always going to Time Warner. Does that irk Moore?

"I find it comical, watching Time Warner try to walk this precarious tightrope." Through contacts in the comics industry, he explains, he has heard that boosted sales of the masks have become a troubling issue for the company. "It's a bit embarrassing to be a corporation that seems to be profiting from an anti-corporate protest. It's not really anything that they want to be associated with. And yet they really don't like turning down money – it goes against all of their instincts." Moore chuckles. "I find it more funny than irksome."

He has a tricky relationship with Time Warner, umbrella company to both DC Comics, which published V for Vendetta in its graphic novel form, and Warner Brothers, the studio behind the big-screen version. Like many of us, Moore thought the 2003 film made out of his late 90s comic strip The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen a great failure, and by the time V for Vendetta had been adapted for the screen, in 2006, he wanted his name removed from the credits; perhaps even from future editions of the graphic novel too. At the time an interviewer asked Moore if he might be "throwing out the baby with the bathwater", and he gave the sort of strolling, storyteller's response that ought to be laminated and distributed to any artist uncertain about giving over their creations to Hollywood. "Well, I don't own the baby any more," said Moore. "During a drunken night it turned out that I'd sold it to the Gypsies and they had turned my baby to a life of prostitution. Occasionally they would send me glossy pictures of my child as she now was, and they would very, very kindly send me a cut of the earnings…"

Today, when we speak, there is still for Moore "a cloud of bitterness" that surrounds V for Vendetta. But with its revival in the context of contemporary protest he has been able to return to the story, drawing cautious pleasure from it for the first time in years. "I don't have a copy of the book around the place, but with the mask everywhere it's made me think back to the work itself, try to figure out why this has lodged in the public imagination."

He sees parallels between the dystopia predicted in the story and the world today. The book foretold the prevalence of CCTV cameras on city streets, for instance; and Moore takes a particular satisfaction in a strand of the plot that seemed to anticipate the sort of internet-based dissent that has made groups such as Anonymous and Assange's WikiLeaks such major agents of protest. "The reason V's fictional crusade against the state is ultimately successful is that the state, in V for Vendetta, relies upon a centralised computer network which he has been able to hack. Not an obvious idea in 1981, but it struck me as the sort of thing that might be down the line." Moore is not computer-literate. "This was just something I made up because I thought it would make an interesting adventure story. Thirty years go by and you find yourself living it."

He is careful to point out that "I have no particular connection or claim to what [the protesters] are doing, nor am I suggesting that these people are fans of mine, or of V for Vendetta." Ultimately, use of the mask may be down to the simple fact that "it's cool-looking. I'm not trying to make a proprietorial statement."

He is also aware of how badly things can go wrong when a fiction of his spreads too far from source. Last year, an unhinged man in Florida went on a shooting spree in a school, spray-painting a "V" symbol on the wall (matching a symbol that appears in the comic and film incarnations of V for Vendetta) before killing himself. "A horrible, pointless episode," says Moore. "So there's always... Now I didn't feel responsible, but..." He does not finish the thought, but trusts the V mask will remain an essentially peaceful tool of protest. "At the moment, the demonstrators seem to me to be making clearly moral moves, protesting against the ridiculous state that our banks and corporations and political leaders have brought us to."

David Lloyd, V for Vendetta's co-creator, has admitted going along to a demo in New York to see the masks in use. The extent of Moore's own activism has been "a good moan in the local pub"; he does not see himself donning a mask ("Be a bit weird, wouldn't it?"). But his sympathies are with the protesters, and there is a clear sense of pride for him that so many people – if not "the 99%" then a great, unignorable bloc – have caused such a stir. "It would be probably be better if the authorities accepted this is a new situation, that this is history happening. History is a thing that happens in waves. Generally it is best to go with these waves, not try to make them turn back – the Canute option. I'm hoping that the world's leaders will realise this."

Back in the early 80s, approaching the end of Vendetta's epic 38-part cycle, Moore was struggling to think of another "V" word with which to title a closing chapter. He'd already used Victims, Vaudeville and Vengeance; the Villain, the Voice, the Vanishing; even Vicissitude and Verwirrung (the German word for confusion). "I was getting pretty desperate," he says.

He eventually settled on Vox populi. "Voice of the people. And I think that if the mask stands for anything, in the current context, that is what it stands for. This is the people. That mysterious entity that is evoked so often – this is the people."

- V for Vendetta

- by Alan Moore

-

- Buy it from the Guardian bookshop

- Tell us what you think: Star-rate and review this book

It all comes back to Moore – a private man with knotty greying hair and a magnificent beard, who prefers to live without an internet connection and who has not had a working telly for months "on an obscure point of principle" about the digital signal in his hometown of Northampton. He has never yet properly commented on the Vendetta mask phenomenon, and speaking on the phone from his home, Moore seems variously baffled, tickled, roused and quite pleased that his creation has become such a prominent emblem of modern activism.

"I suppose when I was writing V for Vendetta I would in my secret heart of hearts have thought: wouldn't it be great if these ideas actually made an impact? So when you start to see that idle fantasy intrude on the regular world… It's peculiar. It feels like a character I created 30 years ago has somehow escaped the realm of fiction."

V for Vendetta tells of a future Britain (actually 1997, nearly two decades into the future when Moore wrote it) under the heel of a dictatorship. The population are depressed and doing little to help themselves. Enter Evey, an orphan, and V, a costumed vigilante who takes an interest in her. Over 38 chapters, each titled with a word beginning with "V", we follow the brutal, loquacious antihero and his apprentice as they torment the ruling powers with acts of violent resistance. Throughout, V wears a mask that he never removes: bleached skin and rosy cheeks, pencil beard, eyes half shut above an inscrutable grin. You've probably come to know it well.

"That smile is so haunting," says Moore. "I tried to use the cryptic nature of it to dramatic effect. We could show a picture of the character just standing there, silently, with an expression that could have been pleasant, breezy or more sinister." As well as the mask, Occupy protesters have taken up as a marrying slogan "We are the 99%"; a reference, originally, to American dissatisfaction with the richest 1% of the US population having such vast control over the country. "And when you've got a sea of V masks, I suppose it makes the protesters appear to be almost a single organism – this "99%" we hear so much about. That in itself is formidable. I can see why the protesters have taken to it."

Alan Moore at the Edinburgh international book festival in 2010. Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian

Moore first noticed the masks being worn by members of the Anonymous group, "bothering Scientologists

halfway down Tottenham Court Road" in 2008. It was a demonstration by

the online collective against alleged attempts to censor a YouTube

video. "I could see the sense of wearing a mask when you were going up

against a notoriously litigious outfit like the Church of Scientology."

Alan Moore at the Edinburgh international book festival in 2010. Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian

Moore first noticed the masks being worn by members of the Anonymous group, "bothering Scientologists

halfway down Tottenham Court Road" in 2008. It was a demonstration by

the online collective against alleged attempts to censor a YouTube

video. "I could see the sense of wearing a mask when you were going up

against a notoriously litigious outfit like the Church of Scientology."But with the mask's growing popularity, Moore has come to see its appeal as about something more than identity-shielding. "It turns protests into performances. The mask is very operatic; it creates a sense of romance and drama. I mean, protesting, protest marches, they can be very demanding, very gruelling. They can be quite dismal. They're things that have to be done, but that doesn't necessarily mean that they're tremendously enjoyable – whereas actually, they should be."

At one point in V for Vendetta, V lectures Evey about the importance of melodrama in a resistance effort. Says Moore: "I think it's appropriate that this generation of protesters have made their rebellion into something the public at large can engage with more readily than with half-hearted chants, with that traditional, downtrodden sort of British protest. These people look like they're having a good time. And that sends out a tremendous message."

It is an irony noted with relish by critics of the protests – one also glumly acknowledged by many of the protesters – that the purchase of so many Vendetta masks has become a lucrative little side-earner for Time Warner, the media company that owns the rights to Moore's creation. Efforts have been made to avoid feeding the conglomerate more cash, the Anonymous group reportedly starting to import masks direct from factories in China to circumvent corporate pockets; last year, demonstrators at a "Free Julian Assange" event in Madrid wore cardboard replicas, apparently self-made. But more than 100,000 of the £4-£7 masks sell every year, according to the manufacturers, with a cut always going to Time Warner. Does that irk Moore?

"I find it comical, watching Time Warner try to walk this precarious tightrope." Through contacts in the comics industry, he explains, he has heard that boosted sales of the masks have become a troubling issue for the company. "It's a bit embarrassing to be a corporation that seems to be profiting from an anti-corporate protest. It's not really anything that they want to be associated with. And yet they really don't like turning down money – it goes against all of their instincts." Moore chuckles. "I find it more funny than irksome."

He has a tricky relationship with Time Warner, umbrella company to both DC Comics, which published V for Vendetta in its graphic novel form, and Warner Brothers, the studio behind the big-screen version. Like many of us, Moore thought the 2003 film made out of his late 90s comic strip The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen a great failure, and by the time V for Vendetta had been adapted for the screen, in 2006, he wanted his name removed from the credits; perhaps even from future editions of the graphic novel too. At the time an interviewer asked Moore if he might be "throwing out the baby with the bathwater", and he gave the sort of strolling, storyteller's response that ought to be laminated and distributed to any artist uncertain about giving over their creations to Hollywood. "Well, I don't own the baby any more," said Moore. "During a drunken night it turned out that I'd sold it to the Gypsies and they had turned my baby to a life of prostitution. Occasionally they would send me glossy pictures of my child as she now was, and they would very, very kindly send me a cut of the earnings…"

Today, when we speak, there is still for Moore "a cloud of bitterness" that surrounds V for Vendetta. But with its revival in the context of contemporary protest he has been able to return to the story, drawing cautious pleasure from it for the first time in years. "I don't have a copy of the book around the place, but with the mask everywhere it's made me think back to the work itself, try to figure out why this has lodged in the public imagination."

He sees parallels between the dystopia predicted in the story and the world today. The book foretold the prevalence of CCTV cameras on city streets, for instance; and Moore takes a particular satisfaction in a strand of the plot that seemed to anticipate the sort of internet-based dissent that has made groups such as Anonymous and Assange's WikiLeaks such major agents of protest. "The reason V's fictional crusade against the state is ultimately successful is that the state, in V for Vendetta, relies upon a centralised computer network which he has been able to hack. Not an obvious idea in 1981, but it struck me as the sort of thing that might be down the line." Moore is not computer-literate. "This was just something I made up because I thought it would make an interesting adventure story. Thirty years go by and you find yourself living it."

He is careful to point out that "I have no particular connection or claim to what [the protesters] are doing, nor am I suggesting that these people are fans of mine, or of V for Vendetta." Ultimately, use of the mask may be down to the simple fact that "it's cool-looking. I'm not trying to make a proprietorial statement."

He is also aware of how badly things can go wrong when a fiction of his spreads too far from source. Last year, an unhinged man in Florida went on a shooting spree in a school, spray-painting a "V" symbol on the wall (matching a symbol that appears in the comic and film incarnations of V for Vendetta) before killing himself. "A horrible, pointless episode," says Moore. "So there's always... Now I didn't feel responsible, but..." He does not finish the thought, but trusts the V mask will remain an essentially peaceful tool of protest. "At the moment, the demonstrators seem to me to be making clearly moral moves, protesting against the ridiculous state that our banks and corporations and political leaders have brought us to."

David Lloyd, V for Vendetta's co-creator, has admitted going along to a demo in New York to see the masks in use. The extent of Moore's own activism has been "a good moan in the local pub"; he does not see himself donning a mask ("Be a bit weird, wouldn't it?"). But his sympathies are with the protesters, and there is a clear sense of pride for him that so many people – if not "the 99%" then a great, unignorable bloc – have caused such a stir. "It would be probably be better if the authorities accepted this is a new situation, that this is history happening. History is a thing that happens in waves. Generally it is best to go with these waves, not try to make them turn back – the Canute option. I'm hoping that the world's leaders will realise this."

Back in the early 80s, approaching the end of Vendetta's epic 38-part cycle, Moore was struggling to think of another "V" word with which to title a closing chapter. He'd already used Victims, Vaudeville and Vengeance; the Villain, the Voice, the Vanishing; even Vicissitude and Verwirrung (the German word for confusion). "I was getting pretty desperate," he says.

He eventually settled on Vox populi. "Voice of the people. And I think that if the mask stands for anything, in the current context, that is what it stands for. This is the people. That mysterious entity that is evoked so often – this is the people."

![Validate my Atom 1.0 feed [Valid Atom 1.0]](valid-atom.png)

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário